Creating a new dungeon campaign can involve–and often does–a lot of world-building. World building is not, and probably should not be, constrained to the sorts of fidelity expected of the sciences, but it must achieve sufficient plausibility and internal coherence that those participating in the experience are not distracted by it; if there are blank areas on the map, and shadowy unexplored corners of the dungeon, they should be enticements to the imagination, not reasons to disengage. The perils and challenges of creating a campaign inspired by the Norse of the Viking period are only magnified, as, on one hand, there may be those whose only encounter with the Vikings is through their portrayal on film, and expect any Viking themed adventure to adhere to that, at least in spirit and feel, regardless of its authenticity, and on the other hand, one may find (a surprisingly large number) of people who know a thing or two (or a lot more) about the Vikings and will be irked by the myriad inaccuracies, anachronisms, or controversial interpretations we will inevitably make along the way. Such is the nature of the beast.

World-building without a coherent framework of what is and isn’t the case is perilous, as one may find, as the accretion of imagined facts born of inspiration becomes more and more unwieldy, and their inter-relationships more and more troublingly incoherent. Ya gotta zoom out and make some decisions.

One such point is to ask, how is society organized, what social relationships are the ones that organize people’s lives and frame the business of life and adventuring, conflict and cooperation. Is there, indeed, any society at all? When the Vikings weren’t pillaging Lindisfarne, what indeed were they doing?

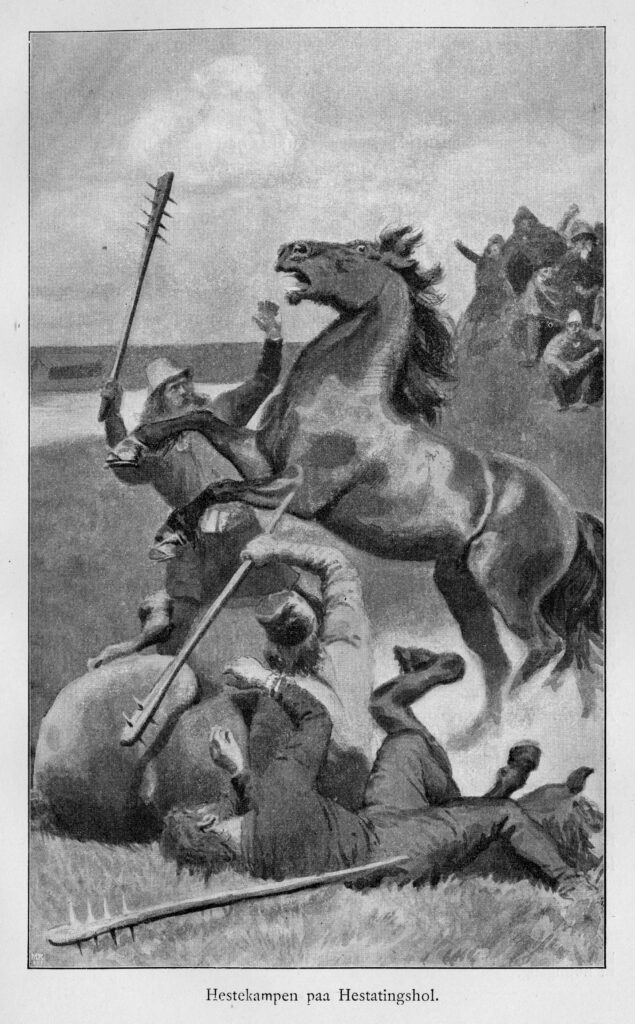

If we look at the various sagas, well, things look pretty chaotic. How can there be a Viking society when everyone is killing each other all the time?

From a modern point of view, the society depicted in Snorri’s narrative resembles sheer anarchy. Armed conflicts, mostly between individuals and alliances based on kinship or mutual interests, are quite normal, and they are conducted in a way in which most means are allowed that may lead to victory, the “rules of the game” being few and vaguely defined. Consequently, very little seems to tie this society together. This impression, however, is only partly correct … First, peaceful means of solving conflicts are clearly underrepresented in the sagas, as they do not lead to important events. Second, in Snorri’s society as in many other traditional societies (see Gluckman, 1965: 140 ff.) armed conflicts are not necessarily against the social order. They are part of it and may even serve to preserve it, in a similar way as the political conflicts that are conducted by peaceful means and according to strict rules in modern society.

Bagge, Sverre. Society and Politics in Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla. 1991. p.121-122

This sense of the fundamental unity of society despite internal conflicts is expressed in Snorri’s comment on the measure Erlingr skakki got passed against his adversary Earl Sigurðr, the leader of the young King Sigurðr Markúsfóstri’s faction. After Erlingr’s victory over King Hákon herðibreiðr renewed the conflict, but had small support and mainly conducted guerilla warfare, to the detriment of the people of Viken. At a popular assembly Erlingr had his adversary condemned to the devil. Snorri is evidently shocked at such unprecedented harshness and calls it an abominable act (ME chap. 10). The reason for this reaction is probably a fundamental distinction between conflicts “within” society, such as conflicts between pretenders and the—very rare—conflicts when society as a whole must defend its fundamental values. To use the sanctions meant for this last category of enemies against one’s normal adversaries is such a horrible break against the rules of the game that it deserves the strongest condemnation in the whole of Heimskringla . By placing his adversaries outside society, Erlingr has broken one of its fundamental rules, the one that unites both parties in a conflict in a fundamental community. Snorri’s reasoning may be compared to the basic idea of modern democratic politics of a consensus concerning the fundamental values of society and politics, despite the constant struggle between different parties.

The fundamental organizing principle then, for world-building, is to decide which sorts of conflicts threaten the social system (or at least are perceived to), and which are part of that social system, to decide upon the fundamental values of the campaign setting, and how to relate those clearly to both the game master and the player participants to create a compelling story.